39 - Exception Handling#

Introduction to Exception Handling#

In a lanugage without exception handling, when an exception occurs, control goes to the operating system, where a message is displayed and the program is terminated.

In a language with exception handling, programs are allowed to trap some exceptions, thereby providing the possibility of fixing the problem and continuing.

Basic Concepts#

An exception is any unusual event, either erroneous or not, detectable by either hardware or software, that may require special processing.

The special processing that may be required after detection of an exception is called exception handling.

The exception handling code unit is called an exception handler.

Exception Handling Alternatives#

An exception is raised when an associated event occurs

A language that does not have exception handling capabilities can still define, detect, raise, and handle exceptions (user defined, software detected)

Alternatives:

Send an auxiliary parameter or use the return value to indicate the return status of a subprogram

Pass a label parameter to all subprograms (error return is to the passed label)

Pass an exception handling subprogram to all subprograms

Advantages of Built-In Exception Handling#

Error detection code is tedious to write and it clutters the program

Exception handling encourages programmers to consider many different possible errors

Exception propagation allows a high level of reuse of exception handling code

Design Issues#

How and where are exception handlers specified and what is their scope?

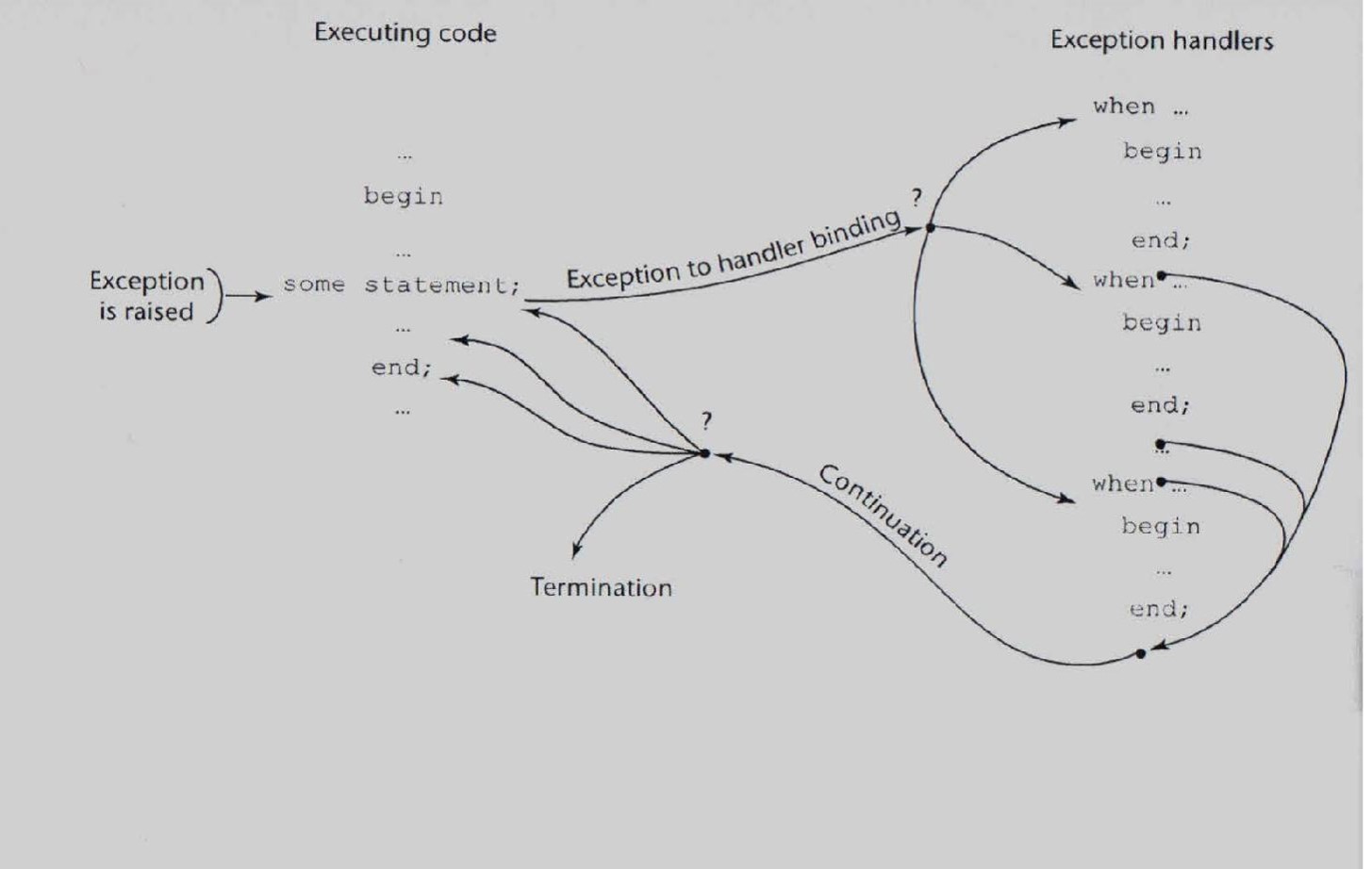

How is an exception occurence bound to an exception handler?

Can information about the exception be passed to the handler?

Where does execution continue, if at all, after an execution handler completes its execution? (continuation)

Is some form of finalization provided?

Are there any predefined exceptions?

How are user-defined exceptions specified?

Should there be default exception handlers for programs that do not provide their own?

Can predefined exceptions be explicitly raised?

Are hardware-detectable errors treated as exceptions that can be handled?

How are exceptions disabled, if at all?

Exception Handling Control Flow#

In C++#

Exception handling was added to C++ in 1990. Its design was based on that of CLU (Cluster), Ada, and ML.

Exception handlers form:

try {

// Code that is expected to raise an exception

}

catch (formal parameter) {

// Handler code

}

...

catch (formal parameter) {

// Handler code

}

The catch Function#

catchis the name of all handlers–it is an overloaded name, so the formal parameter of each must be uniqueThe formal parameter need not have a variable

It can be simply a type name to distinguish the handler it is in from others

The formal parameter can be used to transfer information to the handler

The formal parameters can be an ellipsis (…), in which case it handles all exceptions not yet handled

Throwing Exceptions#

Exceptions are all raised explicitly by the statement

throw [expression];The brackets are metasymbols

A

throwwithout an operand can only appear in a handler; when it appears, it simply re-raises the exception, which is then handled elsewhereThe type of the expression disambiguates the intended handler

Unhandled Exceptions#

An unhandled exception is propogated to the caller of the function in which it is raised

This propogation continues to the main function

If no handler is found, the default handler is called

The default handler,

unexpected, simply terminates the program

Continuation#

After a handle completes its execution, control flows to the first statement after the last handler in the sequence of handlers of which it is an element.

In Java#

Exception handling in Java is based on that of C++, but more in line with the OOP philosophy.

All exceptions are objects of classes that are descendants of the Throwable class.

Classes of Exceptions#

The Java library includes two subclasses of Throwable:

ErrorThrown by the Java interpreter for events such as heap overflow

Never handled by user programs

ExceptionUser-defined exceptions are usually subclasses of this

Has two predefined subclasses,

IOExceptionandRuntimeException(e.g.,ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsExceptionandNullPointerException)

Java Exception Handlers#

Like those of C++, except every

catchrequires a named parameter and all parameters must be descendants ofThrowableSyntax of

tryclause is exactly that of C++Exceptions are thrown with

throw, as in C++, but often thethrowincludes thenewoperator to create the object, as inthrow new MyException();

Binding Exceptions to Handlers#

Binding an exception to a handler is simpler in Java than it is in C++

An exception is bound to the first handler with a parameter is the same class as the thrown object or an ancestor of it

An exception can be handled and rethrown by including a

throwin the handler (a handler could also throw a different exception)If no handler is found in the

tryconstruct, the search is continued in the nearest enclosingtryconstruct, etc.If no handler is found in the method, the exception is propagated to the method’s caller

If no handler is found (all the way to the

main), the program is terminatedTo insure that all exceptions are caught, a handler can be included in any

tryconstruct that catches all exceptionsSimply use an

Exceptionclass parameterOf course, it must be the last in the

tryconstruct

Checked and Unchecked Exceptions#

The Java

throwsclause is quite different from thethrowclause of C++Exceptions of class

ErrorandRunTimeExceptionand all their descendants are called unchecked exceptions; all other exceptions are called checked exceptionsChecked exceptions that may be thrown by a method must be either:

Listed in the

throwsclause, orHandled in the method

The finally Clause#

Can appear at the end of a try construct

Purpose: To specify code that is to be executed, regardless of what happens in the

tryconstruct

A try construct with a finally clause can be used outside exception handling

try {

for (index = 0; index < 100; index++) {

if (...) {

return;

}

}

}

finally {

...

}

Evaluation#

The types of exceptions make more sense than in the case of C++

The

throwsclause is better than that of C++ (thethrowclause in C++ says little to the programmer)The

finallyclause is often usefulThe Java interpreter throws a variety of exceptions that can be handled by user programs

In Python#

Exceptions are objects; the base class is

BaseExceptionAll predefined and user-defined exceptions are derived from

ExceptionPredefined subclasses of

ExceptionareArithmeticError(subclasses areOverflowErrorandZeroDivisionError) andLookupError(subclasses areIndexErrorandKeyError)

try:

# The try block

except Exception1:

# Handler for Exception1

except Exception2:

# Handler for Exception2

except:

# Handler for any exception

else:

# The else block (no exception is raised)

finally:

# The finally block (do it no matter what)

Handlers handle the named exception plus all subclasses of that exception, so if the named exception is

Exception, it handles all predefined and user-defined exceptionsUnhandled exceptions are propagated to the nearest enclosing try block; if no handler is found, the default handler is called

raise IndexErrorcreates an instanceThe raised exception object can be retrieved with

except Exception as ex_obj:

In Ruby#

Exceptions are objects

There are many predefined exceptions

All exceptions that are user-handled are either

StandardErrorclass or a subclass of itStandardErroris derived fromException, which has two methods,messageandbacktraceExceptions can be raised with

raise, which often has the form:

raise "bad parameter" if count == 0

Handlers are placed at the beginning of a begin-end block of code; introduced by rescue

begin

- Statement in the block

rescue OneTypeOfException => e

- Handler

else

- No exceptions

ensure

- Always will be executed

end

Unlike the other languages discussed, in Ruby the code that raised an exception can be rerun by placing a retry statement at the end of the handler.